GUARANTY FUND CHALLENGES

(March 2023)

Editorís

Note: This section was adapted from Critical Issue

Report articles (by Phil Zinkewicz) in Rough

Notes Magazine and other sources.

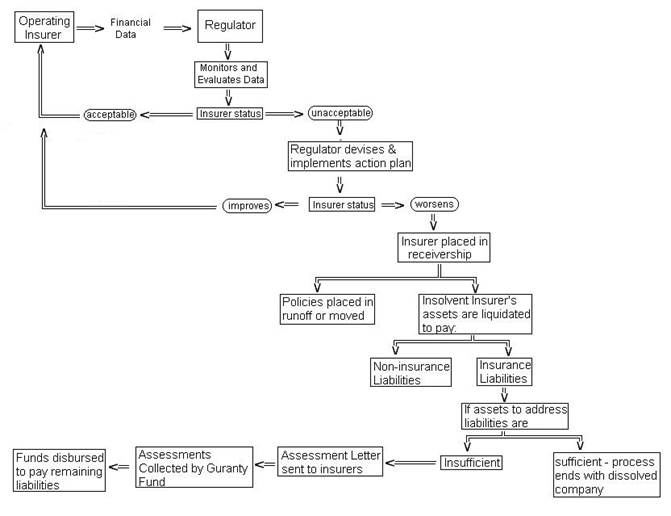

Insurance company

insolvencies are addressed specifically by the state insurance guaranty fund

concept. Under such funds, solvent insurers provide the financial assistance to

handle the financial consequences of a failed insurance company. Ever since the

guaranty fund system was formed, it has performed well.

Existing Fund Approach

|

|

Each state has its

own guaranty fund to handle the claims of insolvent insurers. Guaranty funds

are acquired via assessments on all the other solvent insurers doing business

in that particular state. Seldom are the guaranty funds ever 100% reimbursed.

Since the inception of the guaranty funds, the industry has been assessed

billions more to pay the claims of insolvent insurers than it has recovered

from the estates of such insurers (via the liquidation of their assets).

When guaranty funds

were first designed, their structure and assessment capability were aimed at

the "middle"- in other words, small to medium-sized insurance

companies. State laws cap insurers' assessments at 1% to 2% of their premium

volume in each state.

Related Article:

Guaranty Fund Assessments

Guaranty funds

usually apply to one of the following areas:

- Workers compensation

- Auto insurers

- All other lines of business (other than

auto or workers comp)

Insurers are

assessed within each line to address applicable insolvent insurers.

Capacity Concern

Only a relative

handful of insurers become insolvent in a given year. A.M. Best reported 14

property and casualty insurers that were seriously financially impaired in 2013

and 25 in 2012. †While the average number

of companies that eventually fail is typically low, it does not take much

activity in order to test the capacity of the nationís guaranty funds.

The NCIGF made

available the following information about the systemís largest insolvencies

involving property and casualty insurers.

|

U.S. Ten Largest Insurance Company Insolvencies |

||||

|

Year |

Insurance Company |

Payments |

Recoveries |

Net Cost |

|

(in millions,

rounded up to nearest million) |

||||

|

2001 |

Reliance

Insurance Company |

2,868 |

1,752 |

1,116 |

|

2002 |

Legion Insurance

Company |

1,482 |

453 |

1,028 |

|

2000 |

California Compensation Insurance Company |

1,105 |

354 |

751 |

|

2000 |

Fremont Indemnity

Insurance Company |

1,405 |

724 |

321 |

|

2001 |

PHICO Insurance

Company |

777 |

247 |

529 |

|

2006 |

Southern Family

Insurance Company |

719 |

324 |

395 |

|

1988 |

American Mutual Liability

Insurance Company |

587 |

256 |

331 |

|

1985 |

Transit Casualty

Insurance Company |

568 |

389 |

179 |

|

1986 |

Midland Insurance

Company |

553 |

88 |

465 |

|

2000 |

Superior National

Insurance Company |

538 |

†- |

|

Note: The NCIGF site advises that these figures are not complete as it

depends upon the accuracy and timing of reports submitted by its participating

states. Also, the figures in this version are rounded, so additional errors

appear.

Vulnerability to State

Legislative Actions

All states except

New York use post-event assessments for their guaranty funds. New York, which

uses a pre-assessment approach, also illustrates a problem. Recently, its state

legislature attempted to handle a serious budget deficit by voting to use the

guaranty funds it had already collected for other uses. It then proposed making

additional insurance company assessments to replenish the fund. The move was,

after a huge public and insurer protest, reversed. However, the fact that funds

may be subject to redeployment can cause problems. State governments continue to

deal with a harsh economy and both assessment approaches as well as assessment

ceilings could be changed based on legislative will.

Structure of Funds

In most states,

funds are broken into the major groups of Automobile, Workers Compensation and

All Other Lines. Likewise, assessments are made according to insolvencies that

affect these lines. Some failures could involve insurers that operate in

uncovered lines; in particular, surplus lines offered by specialty carriers that

do not contribute to funds. However, a state would still have to find a way to

deal with losses caused by such an insurer that fails.

|

|

Data Management

Increasingly, claim

data held by insolvent insurance companies exist in a digital format. The guaranty

fund system faces substantial costs in acquiring the ability to transform its

current data management system. It will also increase the amount of resources

needed to create and maintain an adequate level of information security.

Change in Insurer Regulation

Insurance companies

continue to push for greater flexibility, efficiency and reduced costs that

they believe could be gained by federal as opposed to state regulation. Those

assertations aside, the question of federal versus state charters for insurers may

substantially affect state guaranty funds. If federal chartering becomes an

option, it will be important that such insurers be required to participate in

state funds. The nature of an insurerís charter does not change the fact that

it has the potential to fail, endangering the protection of it policyholders in

a given state. Further, they should also maintain their liability for assisting

in the event that other insurers become insolvent. To permit otherwise would

substantially weaken the ability of state funds to act as a financial safety

net.

There is another

option, creating a separate, federal guaranty fund. However, it would have to

deal with issues of expense, administration, taxes and other areas. Further, it

would be duplicative of a viable, existing, system.

Need For A Different Approach?

There are several

possible solutions that might be considered for addressing fund concept

challenges. One would be to raise the cap, either temporarily or permanently,

on assessments insurers pay into the guaranty fund system. Another would be to

move to a single account system, which would mean that all insurers would be

responsible via assessments for an insolvent insurer, regardless of what line

that insurer was writing.

AAI pointed out its

opposition to these. The first approach, the Alliance says, would give state

regulators incentive to delay decisive action with respect to a financially

troubled insurer. "Why take quick action to declare an insurer insolvent

and limit the fallout if the industry's assessments are subject to expansion to

clean up the mess. In addition, many times 'temporary' increases in assessments

become permanent."

As for the second

approach, the Alliance says that it is unfair to assess insurers for insolvencies

in lines they do not write. Rather, the Alliance supports an approach already

in place in Rhode Island. This approach, says the Alliance, provides that money

be borrowed among the guaranty fund accounts when there are capacity problems.

The money borrowed must be paid back to the accounts--with interest--within 10

years.

"If, for

example," says the Alliance report, "the workers compensation account

is maxed out, the auto account can be assessed; but the funds generated are

considered a 'loan' to the workers compensation account. Under this system,

after 10 years, if the loan is not paid back through continual assessments on

the workers compensation account, the loan is considered uncollectible; but

companies may still obtain some tax benefits in terms of deductions for uncollectible

debts."

Other ideas could

include creating a federal fund (discussed above), adding laws that control how

funds are used (to make them less vulnerable to plunder during state budget

shortfalls), creating a federal fund that supplements state funds and expanding

or creating state funds that handle surplus lines insurer insolvencies.